In conversation with filmmakers behind hip hop documentary ‘The … – Rough Draft Atlanta

</p>

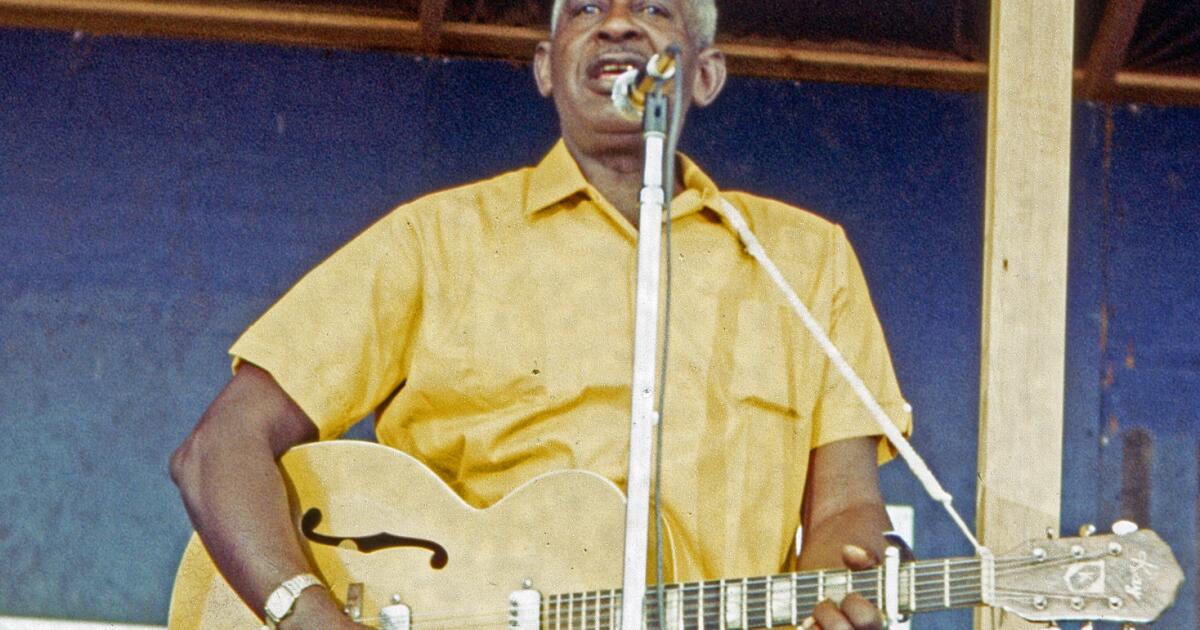

<p>” data-medium-file=”https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?fit=450%2C253&quality=89&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?fit=780%2C439&quality=89&ssl=1″ decoding=”async” width=”780″ height=”439″ src=”https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?resize=780%2C439&quality=89&ssl=1″ alt=”Killer Mike in concert. Killer Mike is one of the artists featured in the AJC documentary “The South Got Something to Say.”” class=”wp-image-193135″ srcset=”https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?resize=1024%2C576&quality=89&ssl=1 1024w, https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?resize=450%2C253&quality=89&ssl=1 450w, https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?resize=768%2C432&quality=89&ssl=1 768w, https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?resize=600%2C338&quality=89&ssl=1 600w, https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?resize=400%2C225&quality=89&ssl=1 400w, https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?resize=706%2C397&quality=89&ssl=1 706w, https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?resize=150%2C84&quality=89&ssl=1 150w, https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert.jpg?w=1200&quality=89&ssl=1 1200w, https://i0.wp.com/roughdraftatlanta.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/AJC-Films_Killer-Mike-in-Concert-1024×576.jpg?w=370&quality=89&ssl=1 370w” sizes=”(max-width: 780px) 100vw, 780px” data-recalc-dims=”1″/><figcaption class=) Killer Mike in concert. Killer Mike is one of the artists featured in the AJC documentary “The South Got Something to Say.”

Killer Mike in concert. Killer Mike is one of the artists featured in the AJC documentary “The South Got Something to Say.”“The South Got Something to Say,” a documentary about the rise of Atlanta hip hop from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, premieres Nov. 2 at 7 p.m. at Center Stage Theater.

Directors Ryon and Tyson Horne, along with AJC reporters DeAsia Paige and Ernie Suggs, conducted more than 60 interviews with hip hop icons, music producers, politicians, and more to get to the root of Atlanta hip hop’s influence throughout the world. Interviewees include the likes of Killer Mike, Dallas Austin, Goodie Mob, and Mayor Andre Dickens.

This project might culminate with the documentary, but the AJC has been posting features, articles, and think pieces about the legacy of hip hop in the lead up to the premiere. On the day of the premiere, there will be different panels and discussions about how Atlanta hip hop has evolved and how it affects everything in its atmosphere.

Tickets for the premiere are available online. The film will be available for streaming on the AJC’s website on Nov. 3.

Ahead of the premiere, Rough Draft Atlanta spoke with Ryon and Tyson Horne about the making of the documentary. This interview has been edited for length and clarity, as well as spoilers for the film.

Could you talk about the inception of this project and how you two came on board?

Tyson Horne: The inception was it being the 50th year of hip hop anniversary. Andrew [Morse], the new publisher … he had just made a mention of, maybe we should do a story on DJ Kool Herc, who has been attributed as being one of the founding fathers of hip hop. We were like, okay that’s cool, because he’s from New York, and we’re actually from New Jersey. But then we said, no. We’re in Atlanta. We’ve been here for a long time now, and Atlanta has been very instrumental in the music industry and in everything else. So we were like, maybe we should do it from the Atlanta perspective.

Ryon and I, we have a family filmmaking company, and we were like, hey – let’s present this like we would any other production. We presented a deck to leadership and Andrew. He looked at it and he was like, you guys can do that? And we were like, yeah, we can do that … That’s how it started.

You start this documentary with The 1995 Source Awards, with OutKast winning Best New Group of the Year. From there, you go back in time and talk about everything leading up to that moment. Why did you choose to start with that moment at The Source Awards?

Ryon Horne: We start with The Source Awards because, if you know anything about hip hop in Atlanta, a lot of people think that hip hop in the south, or in Atlanta particularly, started with OutKast. And also, that night was such a pivotal moment in history, period. You had two coasts battling for dominance. The year before, Tupac had performed there, at The Source Awards. So there was a lot going on that night. And here, during these coasts brewing – which resulted in two of hip hop’s biggest figures being killed years later – this night was happening, and out of nowhere, OutKast comes and makes their presence known. But at the same time, before that night, there was so much that happened in Atlanta, in hip hop.

The name of the film is “The South Got Something to Say.” That phrase was mentioned that night. But we wanted to kind of show, like Speech [cofounder of the hip hop group Arrested Development] says, the South was saying a lot. That’s kind of why we looked at that moment, as one of the most pivotal moments in hip hop history period, but definitely one of the most pivotal moments in hip hop concerning the south.

I thought it was really interesting how this documentary pulls so many different threads outside of the music together, from politics, to the way the strip clubs played a role – at the beginning, there’s even a small section on the Atlanta Child Murders. I’m interested in how the research process was for you both and how you navigated pulling all those different threads together.

Tyson: I want to speak on that one, because I think it’s unfair for Ryon to speak for himself [laughs]. I think that there are two parts to that. One, the good thing about Atlanta is everything down here is truly a melting pot, so everything kind of blends together. It’s a small town. Everybody knows everybody. Even if you’re a Grammy Award winning musical artist, you’ll still probably be hanging out with the mayor, or a politician of some sort.

The biggest bulk of everything when we first started was trying to pull all this together, because there’s so much information and so much that we got out of everybody, because of our relationships with everybody, so they were able to open up and give us more. So a lot of these storylines have been threaded out throughout time, and a lot of people have heard these stories to some degree here and there. But Ryon was able to, through the editing, pull it together in a way that it felt like a seamless story as opposed to too much information coming at you in a way that you can’t digest everything.

So, just to take a step back and look at it from that perspective, it’s one thing to have all the information, but it’s another thing for a team to pull it together, and someone to actually sit down and drive. I always call the editing process driving, and Ryon’s at the wheel driving. For him and his decision making – to turn left, turn right – in the storytelling, that was pivotal. I just think that was done really well.

Another thing that struck me about the story – you know, I’m from Atlanta, a little younger than when this was all taking place, but I generally knew the names and the way things started. But I didn’t realize just how young everyone was. I think at one point, Dallas Austin said he was producing when he was in high school. From your perspective, do you have any ideas as to why everyone started out so young?

Ryon: I think back to myself, and Tyson can speak to this certainly too … I know for me, when I was young I had aspirations of being a dancer, right? I wanted to dance and dance and dance, and me and my friends would always imagine being these big hip hop dancers, and stuff like that back in the day. We would practice at our house – you know, my friend’s mom’s house, or my apartment with my mom. I think about it like, back in those days, these kids had aspirations of doing something, but not knowing that they were going to change the landscape of an entire region and be influential in the entire world.

One of the things about this documentary is of course we say – this happened, this happened, this happened. But we also want to say why this happened, you know? The reason why the Dungeon Family was able to create some of the most profound music in music history is because these were young kids coming to this “dungeon” – they called it a “dungeon” – but coming to [record producer] Rico Wade’s mom’s house in the basement, and they were just creating. They had a safe place to just create. That’s all they had to do, was go downstairs in that small little area and just create.

I think when you have safe places for kids to really be creative and be themselves, and focus on what makes them happy – the skating rinks made these kids happy, and going to parties and stuff made these kids happy, they felt safe – that’s when you get some of the best creative things that we’ve seen happen. With Dallas and Jermaine Dupri – Jermaine Dupri, I mean, his father Michael Mauldin created a place for Jemaine to discover hip hop. He put him on the tour, he danced with [hip hop group] Whodini and witnessed the growth of Run DMC, one of the greatest groups of all time. He witnessed all that firsthand. Then to come home as a teenager and start creating, his parents gave him that space to create. I think that was one of the things that I took away from this. is that when you have a safe place for kids, they could create something magnificent.

Tyson: Jermaine Dupri made a good statement in the film – I don’t know if we added it in or not, but he did say that the culture of hip hop and hip hop in general is the one field where it can make anyone feel like they can do it. You know, I can do that. I can tell my story over music, or I can rap, or whatever it may be. When Ryon was talking about a safe space, at a certain age, kids are just like – what are they going to be into? And if they’re not into sports, or if they’re not into, I don’t know, the debate team or something like that, what are they into? You’re listening to this music, you’re at the roller skating rinks, and it just becomes ingrained in you. It’s just something about hip hop that allows people – because Ryon was dancing, I was rapping at a young age … there’s no training or schooling for being a rapper. You just follow and look at the influences that you see, and then you try to emulate that. I think it opens up the platform for people to say, I can do it, at any age. That’s why you probably get a lot of young people doing it.

There’s a lot of focus on the women who were important to hip hop in Atlanta in this documentary. Obviously, things have gotten better in that arena, but I wondered, do you think that the women who helped pave the way back in the day get the credit they deserve now, or is there still room for growth?

Tyson: Definitely room for growth. We highlight that. Our co-writer, DeAsia Paige, when she came on board, that was one of the things that she brought to the table as far as just making sure [there was an] emphasis on, a spotlight on female artists in the industry, on the mic and in the executive rooms.

One of the first female rappers that I was aware of is MC Roxanne [Shante]. Even back then, how that whole story came about was, you had these guys rapping about this girl named Roxane, and they were pretty much dissing her on record … So when she came out with an album, her album was basically standing up to these three guys, and rapping against them to just try and say, hey – you’re not just going to talk about me that way. It’s always been that in hip hop for women. They’ve always had to show that they can do it and do it better, that type of thing. I think there’s a lot of room for growth in that area, still.

Ryon: With Atlanta hip hop, a lot of the women that were most monumental in the growth of hip hop were people like Shanti Das, who helped get the word out, who marketed OutKast’s albums. Her quick thinking and her quick understanding of how people would connect to a group like OutKast is what helped get them on the national stage. Those were the things that women contributed to hip hop, and were the most needed, because I mean, without Shanti, we don’t know how well they would have been accepted. And the fact that she was there in the room sitting next to them on that fateful night shows she was there for the long haul.